This is an antique violin marked "HOPF" on the back, but it's generally referred to as a fake Hopf violin (in the same way that you can buy a Stradivarius copy today). The real ones made by this 17th century family are marked only on the interior, and they are far more valuable. This one is somewhat poorly built (with no interior corner blocks), and there are several other small issues with it, such as a curve to the neck, and very poorly (crookedly) drilled peg holes. Another dead giveaway that this was originally a cheap German made violin is the fact that the fittings on it were made from cheap woods. I'll repeat this with the accompanying photos below, but the fingerboard was PINE (which is absolute garbage because it needs to be a hardwood at the bare minimum - ebony being the preferred choice), and the pegs (the one original one that was left) and the tailpiece were maple stained/painted black.

All that being said, it's still an OLD violin, probably from around 1900. This is the kind of violin you are likely to come across if your uncle/father/grandmother etc. happens to have an old violin lying around somewhere. Some are better than others, but generally all old violins will have a decent sound because the wood has aged, they've gathered patina, they were played frequently, and most of all: they were hand made. The variations in thickness, as well as the hand varnishing both add significantly to the quality/desirability/sound of a violin. Modern mass produced violins are cut by CNC and because they are too perfect/precise, they tend to have a certain generic sound to them that violin experts can pick up immediately. My ears aren't that well trained. Once this one is playable, it should have a fairly mellow sound.

Anyhow, I picked up this poor little thing all battered and abused from a local thrift shop for 25$ CAD + taxes. I'd say that's a pretty darn good price. It came with a pretty beat-up/ruined bow, which I might also try to repair.

One-piece flame maple back with a two-tone colour.

The top was badly gummed-up and dirty. The area where the bridge sat was also very badly scratched down to bare wood.

The tailpiece had also scratched up the top.

The SEVERELY worn down pine fingerboard. Obviously this instrument was played a LOT.

This was after I repaired/blended and touched-up the top. There were also wear marks along the edges of the top. It's not perfect, and there are a few blotchy areas, but I wanted to preserve as much of the character/patina as possible.

I did not do very much with the back. Mostly just a cleaning and wax polish.

The top had at least two very bad cracks in it (which eventually ended up being 4 cracks), so I had to separate it to repair it. You can see how there are no corner blocks in the pointed corners.

I discovered a very alarming problem with the violin's top, and I was very glad that I decided to remove the top. The entire bass bar was split and coming loose from the top. There was also a crack along the edge (where the bridge sits).

Interior view. No names, inscriptions, or repair dates. Just dust.

Some of the top repairs were easier to glue than others.

I did look at several violin repair tutorials and fixed it in the normal acceptable current method, which is to install small patch blocks (cross grain glued) made from cedar, and then pared down thin. I also had to slightly sand and re-shape the glue-side of the bass bar for a tighter fit.

Here were the cheap fittings. Painted pine fingerboard, and maple tailpiece stained to look like ebony.

A quick note: when it comes to violins, there doesn't seem to be any real impact what fittings you put on it. Generally it needs an ebony fingerboard, nut, and saddle, but the other fittings are to your choice. The pegs, tailpiece, and chin rest can be any wood you like (Rosewood, Boxwood, and other exotic woods are popular). Some can be carved, or have fancy inlays of shells, ivory or metals. Changing the fittings doesn't seem to affect the value of a violin. For this one, I went through a lot of trouble to track down plain ebony fittings (no inlay or anything, just very plain black ebony).

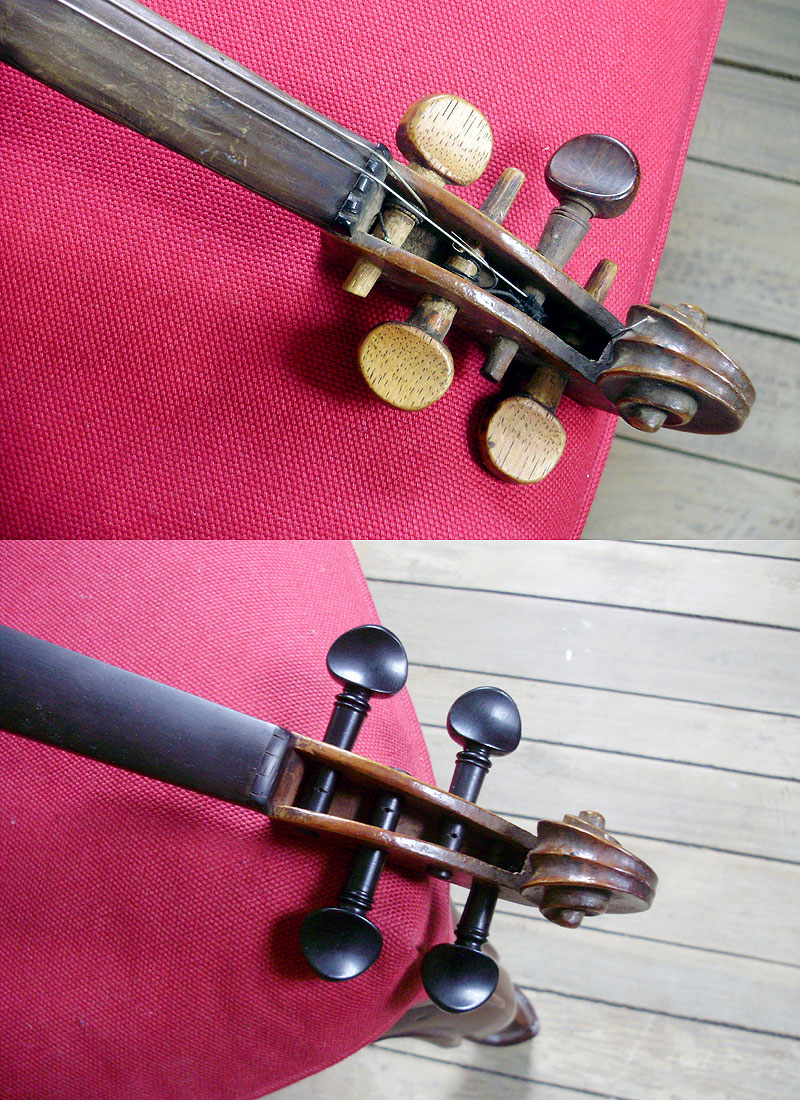

Before and after:

The old pegs were a complete mess. Someone had hand carved some very crude oak pegs for this and they did not work or look good. When I fit the new pegs, I had to enlarge the worn out holes slightly, so I tried to straighten the pegs as much as possible. Most are good, but the bottom one is still quite crooked. Also note the nut (before and after). Yikes!

The saddle that was there was probably a replacement, but it was very badly carved. It didn't need to be replaced, but I did clean it up and sand it significantly. I had a new end button in my new parts, but I chose to keep the old one (this is the only part of the old fittings I kept because it was actually ebony).

The top had two small chunks broken from the edge that I was able to patch. One is nearly invisible, but the other one shows a little bit.

A close up of just the pegbox:

Hand carved and antiqued bridge

That's it. I may post a photo of it again once it's strung.